Your Guide to the Kinetic Chain

The kinetic chain principle is a basic knowledge point which can significantly help you in planning and programming. I highly recommend seeking the professional assistance of a Personal Trainer. It’s a concept used by physical therapists in rehabilitation, instructs fitness professionals in range of motion of the body, and is otherwise incredibly effective in bringing out positive outcomes, whether that’s healing or improving a person’s physical abilities.

But, what is the kinetic chain? How can you make assessing the kinetic chain a better part of your own personal toolkit for training? Having a basic understanding of the kinetic chain for different muscle groups will allow you to not only see where you can improve, but will also give you the insights you need to take it to the next level. Remember, in general, Personal Trainers are not sports medicine professionals and really need to make sure that they are not trying to rehabilitate injuries or do some other thing that lies outside their scope of practice. Always consult with a medical professional when needed.

In order to make use of the concept of the kinetic chain, we first must understand it. So, knowing that, let’s get started.

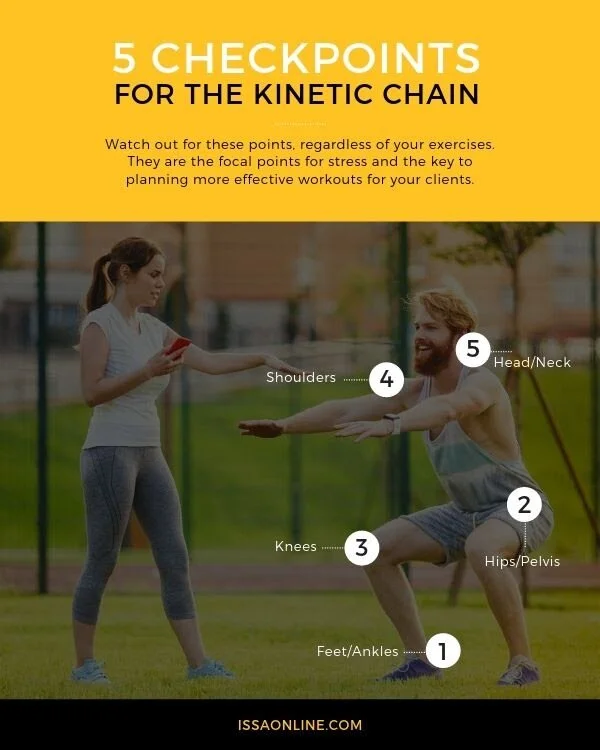

Kinetic Chain Checkpoints

Overall, the kinetic chain comes from the idea that our muscles and joints present a system, similar to an artificial machine, and is used to more effectively and professionally describe the movement processes of the human body. You can see why it would be used in physical therapy.

The kinetic chain is composed of interconnected and overlapping segments which produce force by pushes or pulls and are a prime component of muscle activation. One of the most common issues with the kinetic chain is simply understanding it, which is why we’re trying to break it down here.

To bring it down to Earth, one of the best ways to describe it is in its own checkpoints. These are the links in the chain, from which most of the systems are formed—the major joints. They include, from bottom to top, the feet and ankles, the knees, the hip and pelvis, the shoulders, and the head. These are the linking points, or checkpoints, for the kinetic chain.

The musculature in between is a core component, and the interactions between the joints and muscles are, essentially, the basis of the concept.

Open Versus Closed Kinetic Chain Exercises

At some point, all the joints are major weight-bearing joints. For instance, in a pushup or a bench press, the shoulders are bearing the bulk of the movement, allowing the intervening muscle groups in the upper body to complete repetitions.

In this, though, there are two types of chains—closed and open. The difference between the two comes down to the terminal joint in the chain being either stopped in place or moving. For instance, in a bench press, the arms aren’t pressing against the ground or anything that’s stationary. The motion is free flowing. This makes the movement an open kinetic chain exercise.

A closed kinetic chain, on the other hand, is where the extremity checkpoint is stationary. For this, think about the pushup, where your hands are pushing the body off the ground. The hands and feet are stationary and provide the basis for power in the movement. It also engages multiple, overlapping sets of muscles and joints, another key aspect of a closed kinetic chain.

Taking Closed Kinetic Chains Deeper

Now that we know the basic definition of the closed kinetic chain, let’s dig a little deeper and go into the benefits of this type of exercise.

One whole-body kinetic chain exercise would be the overhead squat. In this, the shoulders are supporting weight above the head, core stabilizers are keeping the body rigid to perform the movement, large muscles like the quadriceps are put to use, and hip flexion is occurring. Notice how all of these constitute overlapping systems that will help with both muscular strength development and postural control. The feet are planted firmly on the ground, the terminal joint stationary, thus making this a closed kinetic chain.

In closed chains, because one end is terminal, you tend to get more stability from it, as it forces a more sophisticated engagement of your muscle groups.

The Open Kinetic Chain

Remember that an open kinetic chain is based on the distal segment being free flowing. So, for this example, we’ll use a leg extension. In this exercise, the foot is in motion. It isn’t pressing against the ground or anything, and it flows freely on one axis.

With this, you will get knee extension and knee flexion, shortening and lengthening the contraction of the muscle tissue both above and below the joint. However, it only moves on one axis.

This is great when it comes to isolating a particular muscle, or when a person is trying to rebuild strength in a particular area of the body. So, think of those who play a sport or compete in some way that may have an imbalance in one side of the body, and also people who have recovered from an injury to the point where they have the ability to start training again.

Why It Matters

When you think about the issues that people face, it can be pretty evident that no two are exactly alike. Your programming needs to reflect this. It can also help you look at the body like a map, and use corrective exercises to help with imbalances. If one needs to build strength in the lumbar spine but has health concerns, you might want to avoid some open kinetic chain exercises where the extremity is free floating—like back extensions.

Furthermore, if a person might have ankle instability, or has suffered several ankle sprains in the past, you might want to consider this when it comes to their ability to do closed kinetic chain exercises in terms of heavy squats or lunges.

Pain doesn’t do any good for anyone. So be extra careful when you’re planning what you will be doing day in and day out. Use the kinetic chain as a guide when you’re planning, based on your history and goals. This is the surest way to find success!